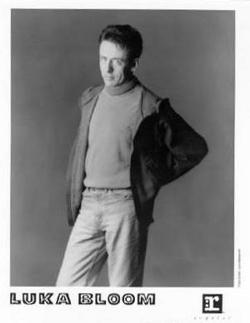

A Talk with Luka Bloom

on Romance, Cycling and Celtic Rap

There's no point in looking for a label to pin on the riveting, kinetic and wholly original music of Luka Bloom. Anchored to an awesome, thundering acoustic guitar technique, the music of this extraordinary artist mixes rap, romance and Celtic passion to create a body of work that consistently defies the pat and predictable.

It's a situation not about to be remedied with the release of Acoustic Motorbike,

Luka Bloom's latest Reprise Records release and the follow-up to his critically acclaimed 1990 debut album,

Riverside. A collection of original songs that spawned lavish praise and

earned Bloom a fervent following on both sides of the Atlantic, Riverside set the stage for the diverse musical

delights that comprise Acoustic Motorbike.

It's a situation not about to be remedied with the release of Acoustic Motorbike,

Luka Bloom's latest Reprise Records release and the follow-up to his critically acclaimed 1990 debut album,

Riverside. A collection of original songs that spawned lavish praise and

earned Bloom a fervent following on both sides of the Atlantic, Riverside set the stage for the diverse musical

delights that comprise Acoustic Motorbike.

Where else could one find L.L. Cool J's rap classic, "I Need Love" accompanied by a traditional Irish drum; a version of "Can't Help Falling In Love With You" that breaks through the crusted cliches to reach the heart of Elvis; a percolating bicycle tour through the Western Irish countryside or an anthemic evocation of Native American majesty?

Where else indeed? From his Dublin home, Luka Bloom recently spoke of these and other matters in a conservation as penetrating and perceptive as the music he makes.

Q: You've been referred to as a very romantic artist. How do you feel about that?

Luka: I'm very wary of words like romantic. In musical terms I associate it with a sort of unreality. My romance has an edge, with a view to what's actually going around us. It's tempered, I suppose, with a certain amount of despair about the state of the world we live in. There's a darker, edgy side of my work. I guess I am a romantic, but not a deluded romantic.

Q: Having said that, you also covered a very romantic rap song. How did you come to record L.L. Cool J's "I Need Love"?

Luka: I'd actually performed the song for a few years perviously in concert. My interest in rap music initially came from my desire to find other musical forms that I could explore and incorporate into my own style. I became interested in rap, first through The Jungle Brothers, whose rap weren't just political, but very musical and often humorous. I decided to take a shot at using spoken lyrics over my particular brand of guitar playing, so I scoured rap material until I came up with L.L. Cool J's song. It was very poetic, very romantic and it was also the most difficult song I ever tried to learn, even though my version is completely different from the original. Rap has been given a bad rap, I think, by people who tend to regard it as simplistic. I find the rhythms and phrasing, from a purely technical point of view, phenomenally sophisticated. It's very hard to coordinate the music with the lyrics and still capture the emotion. The recorded version of "I Need Love" uses a traditional Irish drum called a bodhran, which is played by brother Christy.

Q: "Bridge Of Sorrow" is another song which uses rap elements.

Luka: After "I Need Love" I started writing my own spoken lyric songs. "Bridge Of Sorrow" utilizes both spoken and sung lyrics. It's a way of drawning on the rap experience, while still making it my own.

Q: What have you been up to since the release of Riverside?

Luka: I toured virtually non-stop through most of 1990, playing in the U.S., Canada, Britain and Europe. I found especially receptive audiences in the U.S. and the Low Countries. People there seem very quick to pick up on new things. I'm primarily a live artist who makes records, not a recording artist who performs and as a result it takes time for the word of mouth to filter down.

Q: How did American audiences perceive you?

Luka: I made a point of playing places where you wouldn't normally expect to find a solo acoustic singer: very funky bars and some rock venues. I did an East Coast tour which we called "An Irishman in Chinatown" and followed it up with some West Coast dates that we called "An Irishman in L.A." I lived in America for a few years and toured with The Pogues, Violent Femmes and the Hothouse Flowers, so audiences weren't totally unprepared for what I do. I had something to build on and, as a result, virtually every date was a sell-out. It was very gratifying.

Q: Does your live sound differ from what you do in the studio?

Luka: I want to get the energy of my concerts on record and that's certainly the case with the new album, which is much more raw and immediate than the first. It's a less polished sound, which I think really makes it more accessible. People who make interesting first albums and get larger budgets the second time around sometimes feel they have to indulge themselves a little more. I wanted this album to be a reflection of who and what I am as a live performer.

Q: What happened after you finished touring?

Luka: I came back to Ireland, where I decided to relocate after living in the States since late 1986. A lot of interesting things had happened, musically and culturally since I left. I really wanted to connect with that fresh spirit that new feeling of openness to original Irish music. Things had definitely changed.

Q: Did you start recording immediately?

Luka: I hid myself away in a small cottage in the west of Ireland and started writing. That was also where I took up cycling, which gave me the inspiration for the album's title track. I think the image of an acoustic motorbike really symbolizes what my music is about. It's pedal powered, but it's fast, with a lot of movement and energy. Acoustic motorbike is to my music what a Harley Davidson is to rock 'n' roll.

Q: When did recording get underway?

Luka: In March of this year, for about two months. I cut it in Dublin with an Irish producer, Paul Barrett and Irish musicians, the only exceptions being the guitar player from my first album Ed Tomney and Bob Riley, the drummer from Grace Pool. They both came over from the States.

Q: Another interesting cut on Acoustic Motorbike is the "Listen To The Hoofbeat". How did that come about??

Luka: I saw a TV documentary which focused on 100th anniversary of the massacre at Wounded Knee and the commemoration of the forced march by Native Americans as they are today and their attempts to reawaken their own essential spiritual values. They are a remarkable people and for some time I've had a fascination with Native American history. With the world being destroyed by white European technology and industry, the time is fast approaching when we will look to people like Native Americans to help us try and understand how we're supposed to live on this planet. They don't talk about the environment. They talk about Mother Earth. Maybe we should began to think about the earth in that fashion again. That's the idea of the song. Native Americans, of course, are well capable of speaking themselves. "Listen To The Hoofbeat" is really a call to white people to begin to listen.

Q: You mentioned both a play and a TV documentary as sources for songs. Is that common in your work?

Luka: I find my inspiration from many sources. "Bones", for instance, is a song inspired by a play called 'Road', written by a British playwright named Jim Cartwright. It's set in England during the miner's strike of mid-'80s, a very desperate, desolate time, but it could be about any sort of wasted urban environment and what it's like to grow up with total unemployment, poverty and hopelessness. It's very important to me to be able to connect with the suffering in the world. The last thing the world needs is another guy who's writing songs about lonely nights on the road. Things happen in the course of my life that are of sufficient importance to me that I would consider writing a song about them and including it on a record. But I'm also constantly looking outside myself. That's what makes my job such an exciting prospect. It's a journey into the unknown and I have to keep my eyes and ears open.

© 1992 Reprise Records

© Rena Bergholz - Luka Bloom Page